Conservatives frequently accuse liberals of being out of touch with Americans. It’s an accusation that stings partly because there’s truth behind it: Real evidence suggests that liberal institutions, the Democratic Party chief among them, inhabit a moral universe distinct from that of the median voter.

Yet far less attention has been paid to the disconnect between the right’s intellectual elite and the American public. Liberal intellectuals live in an unrepresentative world, but so too do the right’s thinkers — causing them to develop an idea of America that is largely unmoored from the country most Americans experience.

And in the Donald Trump era, this disconnect may be the more influential one.

This right-wing elite bubble is perhaps most precisely described as two bubbles.

The first bubble is created by the overwhelmingly left-liberal tilt of elite knowledge production industries — most notably journalism and academia, but, to a lesser extent, law and tech. Conservatives in these areas often feel outnumbered and even persecuted in their professional life, creating a sense that the left is far more socially powerful in America than it actually is.

The second bubble is a reaction to the first bubble: the creation of internally homogenous spaces within these liberal fields. These are spaces where conservatives talk primarily with each other about liberals and the left, often exacerbating their shared sense of threat.

Fox News and the Federalist Society are two of the most influential institutions of the second bubble: islands of right-wing thought in fields where liberals predominate. But they are hardly alone. A host of other spaces, ranging from formal institutions like the Heritage Foundation to some billionaire-created group chats, serve as venues for right-wing professionals to talk politics amongst themselves.

There’s nothing wrong with ideological movements hammering out ideas amongst themselves. However, there is always a danger in such spaces of groupthink and caricaturing one’s opponents. Increasingly, both are happening inside the right’s bubble — and warping its view of the country in the process.

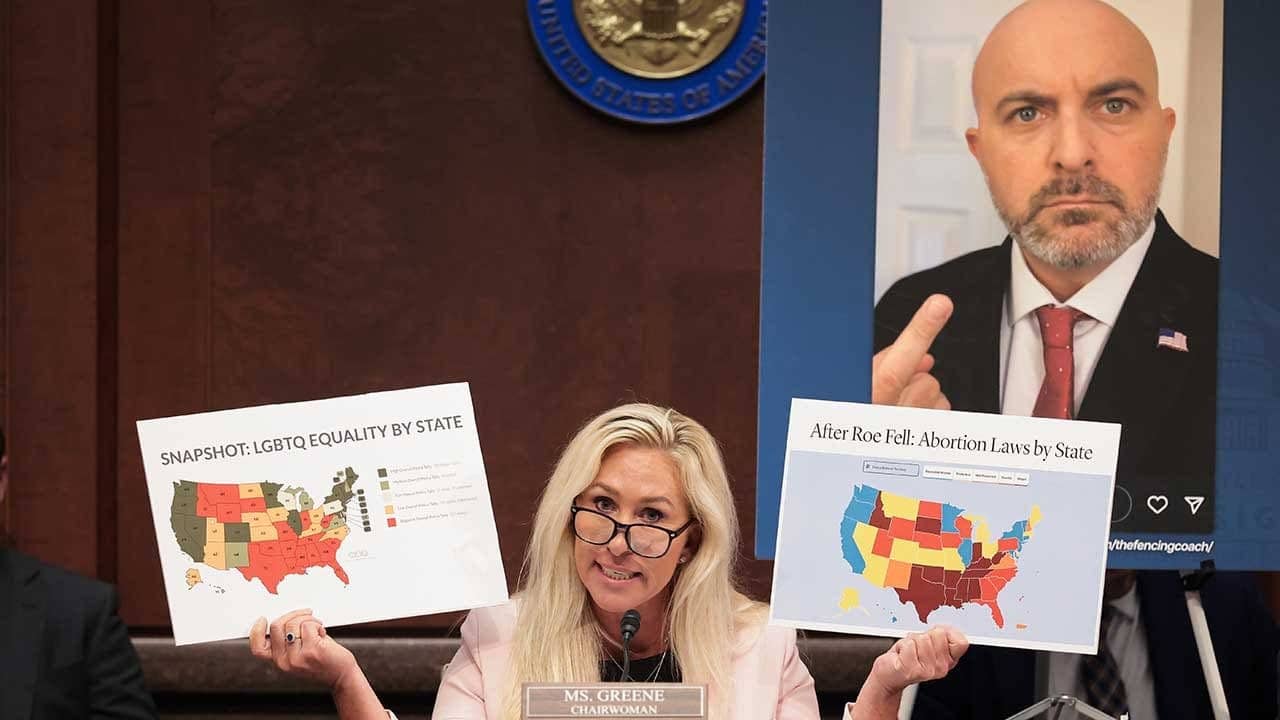

In the past few years, there has been a cottage industry of right-wing intellectuals arguing that American culture and society have become fundamentally hostile to people like them. In their view, the right’s embrace of Trumpian authoritarianism is not an act of political aggression, but a defensive response against a near-omnipotent cultural left intent on wiping conservatives off the face of the earth.

This is not, of course, America as it actually exists. Real America is a place where evangelical Christians are the largest religious group, the Supreme Court has a 6-3 conservative majority, and Donald Trump won the presidency twice.

Yet this caricature of the country has taken deep root among right-wing elites. It is a belief given life by the right’s experiences inside left-wing professions, and then strengthened and radicalized in the spaces they’ve carved out as alternatives.

In prior years, this right-doomerism may have seemed like a sideshow confined to a handful of intellectuals. But in the second Trump administration, its adherents are helping shape policy in a host of key sectors, ranging from immigration to education to science to foreign policy.

The carnage in those areas is, in no small part, these right-wingers swinging axes that have been ground for decades.

What the double bubble has wrought

Generally speaking, most people who write about political ideas professionally are in one of two fields: journalism or academia. The data suggests that these fields really are dominated by liberals and the left. You’re often equally likely to encounter a socialist as a conservative; in some academic fields, Marxists and critical theorists vastly outnumber people on the right.

This can understandably make conservatives in these spaces feel uncomfortable, or even unwelcome. But some of them go much further than that: They argue the ideological culture of the university is in fact the ideological culture of America, and that conservatives writ large are in the same position as the academic minority.

This move is central to the argument of Regime Change, Notre Dame political theorist Patrick Deneen’s 2023 book. One of the foremost Trump-aligned intellectuals — JD Vance endorsed his book, and Pete Hegseth was a former Deneen student — he believes America is being corrupted by left-wing rot that begins in the university.

“Universities…are today in the forefront of advancing new principles of despotism,” he argues. “These educational institutions help shape the worldviews and expectations of the managerial ruling class, who then deploy to a variety of settings where those lessons come to shape most of the main organizations that govern daily life.”

This overheated rhetoric grew out of Deneen’s own experience in the academic bubble. In 2004, Princeton denied him tenure — a decision that he has publicly blamed on anti-conservative discrimination. In 2012, he left Georgetown for Notre Dame on the grounds that the former had become so secular and liberal that he could not feel comfortable there. “I have felt isolated and often lonely at the institution where I have devoted so many of my hours and my passion,” he wrote in a contemporary letter to his Georgetown students.

One can sympathize with Deneen’s feelings of alienation without accepting his caricature of America as a giant faculty lounge. Yet despite Regime Change’s analytic flaws (you can read my review here), it found friendly reception among many like-minded thinkers on the right, including Michael Anton, a longtime fellow at the pro-Trump Claremont Institute who is currently serving as the State Department’s director of policy planning.

“The main divide in conservative ranks today is between those who see clearly what the Left has done and those who deny it — and attack anyone to their right who notices. Say what you will about Patrick Deneen, he’s on the right — in both senses of that term — side of this divide,” Anton wrote in the Claremont Review of Books.

When Anton speaks of “those who see clearly what the Left has done,” he is not speaking purely in abstract terms. There are discrete and concrete institutions and networks, including Claremont itself, where people who share this sense of being under cultural attack by the left-wing elite. These are places where fantastical pictures of America as a place in the grips of a liberal plot are not seen as caricatures, but bleakly accurate accounts of 21st-century life.

In such spaces, it becomes normal to treat America as a place where right-wing Americans are not just outnumbered, but on the verge of extinction. In one infamous 2021 essay, Claremont fellow Glenn Ellmers writes that “most people living in the United States today—certainly more than half—are not Americans in any meaningful sense of the term.”

For this reason, he argues that “the political practices, institutions, and even rhetoric governing the United States have become hostile” and that “the mainline churches, universities, popular culture, and the corporate world are rotten to the core.” In reaction, he writes, conservatives must prepare for a “counter-revolution,” possibly a violent one — writing that “strong people are harder to kill, and more useful generally.”

Ellmers’s essay reflects a level of radicalism that permeates right-wing intellectual spaces. And now, such ideas are shaping policy.

We know this, in part, because some denizens of the right’s intellectual bubble are now in top positions. Vance is vice president. Hegseth, a longtime Fox News personality, is the secretary of defense. Anton occupies one of the top positions at State, where he serves with Darren Beattie, an aggrieved former Duke PhD who was pushed out of the first Trump White House for associating with white nationalists.

But we also know it because of the policies being put in place. Hegseth, for example, has spent less time trying to fix American warfighting capabilities than waging culture war on alleged leftists at the Pentagon. Beattie is leading an internal inquiry into the political activities of State Department staff that one official there describes as a “witch hunt.”

Perhaps the clearest case is the preoccupation with destroying America’s elite universities through federal funding cuts and revocation of tax-exempt status. The Trump approach here is widely credited to Manhattan Institute senior fellow Chris Rufo, who has made the notion of an America poisoned by New Left radicals in the faculty lounge the central principle of his career as a writer and activist.

“The most sophisticated activists and intellectuals of the New Left initiated a new strategy, the ‘long march through the institutions,’ which brought their movement out of the streets and into the universities, schools, newsrooms, and bureaucracies,” he writes in his book America’s Cultural Revolution. “Over the subsequent decades, the cultural revolution that began in 1968 transformed, almost invisibly, into a structural revolution that changed everything.”

At the end of the book, Rufo (like Ellmers) calls for a “counter-revolution” against the left. The Trump administration’s demolition derby shows us what this looks like in practice.

This story was adapted from the On the Right newsletter. New editions drop every Wednesday. Sign up here.

#Trumps #authoritarian #policies #shaped #intellectual #outcasts

Leave a Reply