On his first day back in the White House, President Donald Trump signed executive orders that ranged from addressing petty grievances to radical overhauls of American democracy. But one of the actions that stood out in particular was his decision to issue pardons and commutations for the people — more than 1,500 — charged with crimes after being involved with the insurrection on January 6, 2021.

At best, these pardons excuse the violence that took place on January 6, and at worst, encourage that kind of violence in the future by essentially promising would-be insurrectionists forgiveness.

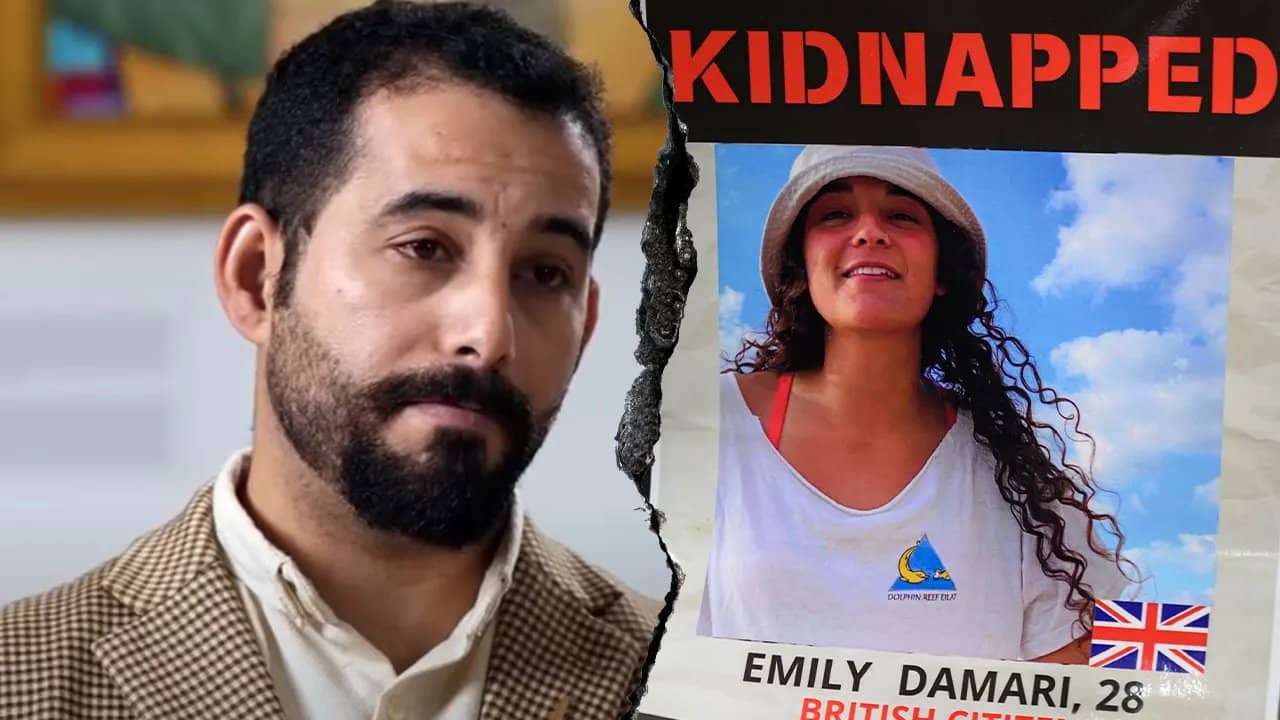

And while some of the organizers and rioters from that day were charged with low-level crimes like trespassing, others faced far more serious charges. One example is Enrique Tarrio, the former leader of the far-right militant group the Proud Boys, who was sentenced to 22 years in prison for seditious conspiracy and other felonies but now walks free. Trump also commuted the sentences of other members of extremist, far-right groups that promote political violence.

The deadly assault on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, was a serious threat to our democracy — a direct result of an incumbent US president being unwilling to concede an election that he clearly lost. It sullied the tradition of the peaceful transfer of power that Americans had come to believe was a guarantee. And now, its participants have been let off the hook.

Trump’s pardons are paradoxical. The January 6 insurrection was a disturbingly undemocratic act, and yet Trump returned to power and pardoned the insurrectionists through democratic means. If anything, it’s an (unfortunate) example of how the pardon power has its own type of democratic legitimacy. In the end, Trump’s decision to let those who rioted in his name out of prison — as he repeatedly said he would do during the campaign — reflects what the electorate voted for and as such, represents the final rewriting of the history of January 6, which the country is, at least for now, willing to forget.

Like it or not, Trump’s pardons were a democratic exercise

The pardon is so important because it is a democratic tool that the public can wield.

For the most part, the public doesn’t have much of a say when federal courts make bad decisions. The pardon power is an exception, giving the electorate a chance to undo convictions or stymie criminal cases that they think are unjust by electing a president who thinks the same and promises to take action. Whether these are actual instances of injustices are real or perceived isn’t the key thing — just because the public wants something, that doesn’t make it right. The key is that the pardon power injects public accountability into the criminal justice system.

For example, on his first full day in office, President Jimmy Carter pardoned hundreds of thousands of Americans who had evaded the draft during the Vietnam War, fulfilling a campaign promise that reflected Americans’ changing mood about the war. Other presidents, most recently Joe Biden and Barack Obama, have also used the pardon in a way that represented a shift in public attitudes by granting clemency, for example, to people convicted of nonviolent drug charges.

In the same vein, Trump’s pardons of those who participated in assaulting the Capitol on January 6 is a reflection of public opinion, even if they are also self-serving. After all, Trump’s actions on Monday didn’t exactly come as a surprise; throughout his 2024 campaign, Trump promised to pardon the insurrectionists (though he often sidestepped the question of whether he would grant clemency to those who assaulted law enforcement officers, and his campaign at one point said that the pardons would be decided on a case-by-case basis). He called those who were convicted “political prisoners,” many of whom, he said, deserved an “apology.” Americans voted for him anyway.

That doesn’t mean that Americans by and large support these pardons. A December poll, for example, showed that the majority of Americans actually oppose them. But since Trump didn’t keep his intentions secret, the place to reject these pardons was back at the ballot box in November — and the electorate made clear that this was a line that Trump could indeed cross.

This distinguishes it from other examples of presidents who have routinely misused the pardon to advance their own corrupt interests with zero input from the public. In his first term, Trump pardoned his cronies and his son-in-law’s father to help himself, for example, and Biden pardoned his own family members. These were all actions that Americans did not have an opportunity to weigh in on. This time, however, the public knew exactly what they were likely to get.

So while the January 6 pardons allow Trump to minimize the damage he inflicted four years ago — making the attack of the US Capitol a forgivable offense, one that he claims the Justice Department unfairly prosecuted — the fact that Trump made pardoning January 6 defendants a signature campaign promise and went on to win the presidency makes this act of clemency a more democratic exercise than his previous actions.

The pardons are a rewrite of January 6

Even if the pardons are flawed or even dangerous — a move that shows tolerance for right-wing political violence and likely emboldens fringe groups — they represent a public that is ready to move on from the assault on the Capitol as though it was just another political protest. Public polling has shown that as the years went by, Americans softened their stance on January 6, with a growing number of respondents viewing it as a more peaceful event than they originally thought and believing that the punishments were too harsh. And by electing Trump in November, the plurality of the electorate seemed to be ready to either, at the very least, forget about January 6 or change the historical record — perhaps remembering it as a display of noble patriotism as opposed to a violent assault on their government.

That’s exactly what Trump’s pardons are: the right’s final rewrite of January 6. They can’t be undone, meaning that the possibility of ensuring full accountability for the events of that day is all but vanquished.

There is certainly something perverse about all of this — that a deeply undemocratic event, an effort to overturn an election no less, is now being rewritten through democratic means. But that is not the fault of the pardon power, which remains a critical tool that presidents ought to use. Instead, critics of Trump’s decision have only this to reckon with: Elections have consequences, and this is just the start.

#Trumps #January #pardons #misuse #executive #clemency

Leave a Reply